** Day 24: Crossed Wires – Simulating a system of XOR, AND, and OR logic gates wired together

Part 1

Just carefully implement the details of what the description says. It'll probably include some dictionaries, and perhaps frozensets.

Part 2

I don't have a purely algorithmic approach to recommend here since I basically just used code as an incremental forensic tool to interactively assess the circuitry.

Specifically, I...

...noted that the problem says gate outputs got swapped, not gate inputs. This is important because it means all gate input connections are correct; only the output connections may be incorrect.

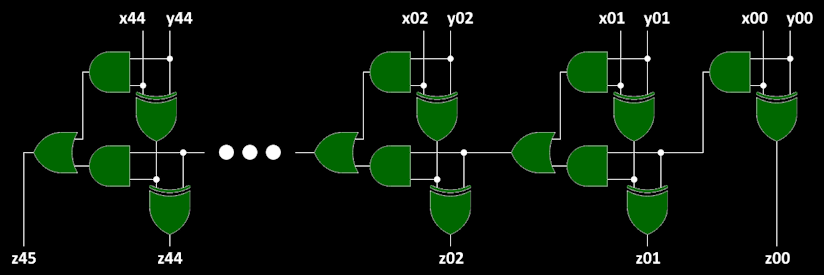

A correctly constructed adder circuit—see below—should have only XOR gates outputting to the z## output wires, except for the most significant bit, which should be an OR gate's output. So, I back-traced all the z## output(?) wires to their respective gates, i.e., those outputting to them. This back-trace identified three incorrectly connected wires (connected to the wrong type of logic gate) for my given problem input data.

I also...

...took advantage of the fact that, since all the gates' inputs are correct, then all of the circuit's x## and y## input wires are definitely correctly connected to their respective XOR and AND gates. This meant I could identify exactly which XOR gates must be connected to output wires, i.e., z## wires—any of them, whether or not they're the correct ones. That is, all those XOR gates not connected to circuit inputs x## and y## wires are supposed to be connected to z## wires for output (except for the least significant bit, which should be connected to all three). From this subset of XOR gates, I identified all those not connected to z## wires, which produced another three results for my problem input data, and I was able to pair these with the previous erroneous-gate-output results to determine three of the four wire swaps.

I then had one more problematic gate-output-pair to identify...

...I corrected the three erroneously swapped output pairs then repeatedly simulated the resulting circuit with carefully selected input test vectors, comparing the results to known-correct results.

Specifically, I ran through inputs of...

...all-zero y## with x## values iterating through a single 1-bit shifted incrementally leftward, which should yield z=x as output, in each case. These inputs exercise the "sum paths" through the circuit.

I also iterated through a single 1-bit shifted incrementally leftward for both x## and y## inputs (x=y), which should yield z=2x=2y (either x or y shifted left once more) as output. These inputs exercise the "carry paths" through the circuit.

Examining those circuit-outputs not matching the known-correct results suggested the gate-outputs for a specific XOR and AND gate should be swapped. I did this wire swap, then re-ran the simulations, and they all passed.

From all these identified problem-wire-pairs, I generated the alphabetized answer.